(Virgin and Child. Castille, between 1340 and 1350. Alabaster with polychrome paint fragments. Federic Marés Museum, Barcelona. Photo T.R.)

To say we have never experienced such a strange Christmas would be an understatement. For the theatre world, and for everyone in general, the outlook for this year’s holiday season –in which the winter solstice and birth of the Christ Child are celebrated– goes against the logic that has always presided over these festivities: family gatherings, unity between people, inviting strangers into one’s home, shared human warmth shared. All of this, today, is prohibited for one objective reason: the Covid-19 pandemic and the dangers of contagion oblige us to isolate ourselves, not to interact with our neighbours, friends and family, to “become strangers” to ourselves. A restriction, furthermore, imposed by the public authorities, so that the obligation presents itself as a veto on contact and community. A situation that has, surprisingly, been accepted without too much resistance on the part of the world’s population, although with some natural exceptions on the whole in a minority. The word ‘strange’ comes from the Latin extraneus, which means ‘from without’, ‘alien’, ‘foreign’, and which derives from exter, ‘being on the outside’. That is to say, we apply a self-imposed condition of being strangers to ourselves, to our own towns or cities, of being inside but outside, of being foreign to our own animal-human nature which tends towards family union and that of the group. For those who hate Christmas and enjoy going against the grain it is heaven, Utopia incarnate! An isolation, at long last, that doesn’t require active rebellion, but is imposed by the very social powers that normally demand we celebrate Christmas. For those who love these days of human warmth and meetings with family and friends it is a severe blow to what keeps society afloat. These moments in the calendar provide respite from the demanding, stressful ‘estrangements’ of everyday working life in urban societies.

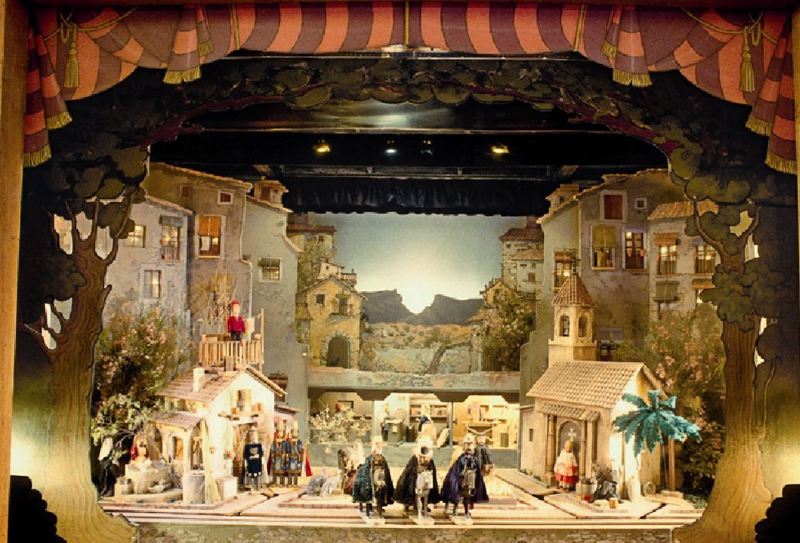

Tirisiti Christmas Crib, Alcoy The Three Wise Men.

For those whose livelihood depends on the theatre, it is the worst panorama imaginable, the world turned upside down, a nightmare come true. The warmth of, and closeness to the audience are substituted by distance and the separation between persons partaking of the ritual. Catharsis goes cold and the mechanisms of theatrical communication are exposed. Everything grates and, all of a sudden, what was considered as a linchpin of our cultural activity –the theatre!– becomes dispensable. Audiences enjoy or make do with shows ‘online’, the digital substitutes in-person events, and everyone says ‘a new era has begun’. A state of ‘exile’ invades us from all sides, everything that until now was normal and beneficial, becomes problematic and questionable. And, most peculiar of all, experts of futuristic sociology enjoy lecturing us on what is going to be normal from now on: relativising the direct person-to-person relationship, incorporating into it the indirect digital relationship. Will the future, really, be like this? Will we live immersed in this contradictory coming-and-going between meeting and distance, between the real and the virtual? Halfway between yes and no, between what we can touch and what we can only see, between the real body and the duplicated image, between two different spaces or times …

Christmas Crib with Pulcinella figures. Pulcinella Museum in Acerra, Italy.