History

Turkish shadow play, also called Karagöz, is an important cultural heritage. It could be described as a micro cosmos, a cross-section of Ottoman culture and social structure combined into a harmonious and many-faceted totality.

As to the question of where, how and when the shadow play came to Turkey, this tradition does not exist in Central Asia and Iran, so it cannot have arrived from there. It’s known that shadow play was introduced to Turkey from Egypt in the l6th century when there is indisputable evidence of its existence here. Evidence of its introduction from Egypt is equally incontrovertible, provided by a history of Egypt entitled Bedayiü’z-zuhbur fi vekaayiü’d-dühur by the Arab writer Mehmed b. Ahmad b. İlyasü’l-Hanefi.

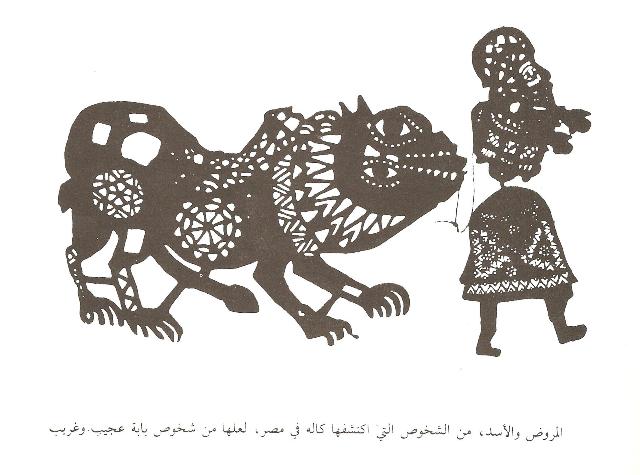

Old Egyptian Shadow

Where the part of this book pertinent to our subject is concerned, it relates that when the Ottoman sultan Selim II conquered Egypt in 1517 he hanged the Mamluk sultan Tumanbay II on 15th April 1517. The shadow player at the palace on the island of Rode in the Nile at Cize re-enacted the hanging of Tumanbay at the Züveyle Gate, including the fact that the rope snapped twice in the process. Sultan Selim was very pleased with the performance, and having presented the player with 80 gold pieces and an embroidered kaftan, said, ‘When we return to Istanbul, come with us, so that my son can see this play and be entertained.’

Another reliable source confirming that the shadow play was introduced to Turkey from Egypt in the 10th century is a work by Ibn Ilias dating from the reign of Yavuz Sultan Selim II.

Old Egyotian Shadow.

The history of Egyptian shadow theatre can be traced back to the 11th century. We find a long account of the shadow play in Egypt by the poet Ömer Ibnül-Fariz, in his Ta’iyyeti’l-Kübra: In the shadow plays described in this poem ships sail on the sea, armies battle on land and sea, camels, cavalry and infantry soldiers pass by. A fisherman throws his net and catches fish, sea monsters sink ships, and lions, birds and other wild animals attack their prey. Almost all of these later featured in l6th century shadow plays in Istanbul. Here too birds fly, wild animals fight one another, ships sail and people are swallowed by a monster. Further proofs of such shared features are pictures discovered by Paul Kahle thought to depict a 13th century shadow play. When we examine these pictures we find that the figures induce a lion, birds, including a stork and ships.

After the introduction of the shadow play from Egypt, the Turks made their own creative contributions, and a very colourful, animated and original new form emerged which was disseminated throughout the Ottoman Empire and its sphere of influence. Sources describing the early Turkish shadow play all date from the festival of 1582, celebrating the circumcision of the royal princes, or dates close to this. The most important document, which did not attract the attention of earlier researchers, and which gives the most extensive and detailed information about the shadow play, is the Surname-i Hümayun, an illustrated account of the famous 1582 festival.

In numerous places in the Surname-i Hümayun we come across the term “hayalbaz”, which is not explained, presumably because everyone knew what it was. The term hayalbaz may have referred to a type of puppet or perhaps another type of performing art, before it came to refer to the shadow play. In a foreign source, although puppet plays are described in several places, the shadow play is described in only one place, as in the Surname-i Hümayun. This foreign eyewitness, although he gives a shorter description than the Turkish writer, had dearly seen the same performance:

“Someone brought a small wooden hut on six wheels, the stage, into the centre. In front of this was a curtain of linen cloth, and inside several lights. Someone made the images move, casting reflections onto the curtain by means of the lights. For example, a cat ate a mouse, and a stark ate a snake. As well as these, two people talked together using signs made with their fıngers like mutes, and similar things. One chased, another ran, and so on. Watching all these would have been most delightful if the strings pulling the images here and there had not been visible.”

There are many common features between the two texts. For example, the Surname-i Hümaylbı description also mentions a cat and mouse, and a stork and snake. Both texts say that the images were moved by means of strings. It is possible that the audience mistook the shadows of the sticks moving the figures for strings. Prologues involving animals were still being shown at the end of the 19th century.

According ta the Surname-i Hiimayuıı, a prayer was recited to the reigning sultan at the beginning of the play, just as it was in Karagöz. Here birds fly, beasts of prey are shown in combat, lovers bend their heads before beautiful girls seated on ornate thrones, singers sing beautiful melodies, the wind snaps great galleys in half, people eat and drink at social gatherings, various flowers are shown growing in meadows, various fruits grow regardless of the season, and after the scenes of the cat and mouse and the stark and snake, a horrifying monster arrives and swallows up all the people.

According ta the Surname-i Hiimayuıı, a prayer was recited to the reigning sultan at the beginning of the play, just as it was in Karagöz. Here birds fly, beasts of prey are shown in combat, lovers bend their heads before beautiful girls seated on ornate thrones, singers sing beautiful melodies, the wind snaps great galleys in half, people eat and drink at social gatherings, various flowers are shown growing in meadows, various fruits grow regardless of the season, and after the scenes of the cat and mouse and the stark and snake, a horrifying monster arrives and swallows up all the people.

In the 17th century Karagöz attained its familiar form. For this century there is extensive evidence, including the account by Evliya Çelebi and others by foreign travellers to Turkey. The most detailed information about the shadow play in the 17th century is provided by Evliya Çelebi. It is in his book that we find the names Karagöz and Hacivat mentioned for the first time, (he subjects and characteristics of the plays, the poems, which were recited, and the famous shadow players of the age.

A much-debated subject is whether Karagöz and his friend Hacivat were real people. These two protagonists of the shadow play became so ensconced in the hearts of the people that they wished to envisage them as people who had really lived, and various stories were told about them that seemed to prove this. According to one of these, Hacivat was a stonemason and Karagöz a blacksmith during the reign of Sultan Osman in the early 14th century. While the pair was working on the construction of a mosque in Bursa they distracted the other workers with their witty repartee, so that the work fell behind schedule and the sultan ordered their execution. This, however, collides with the best-proven theory that Karagöz arrived from Egypt in the 16th century.

About its earlier history there are various theories. According to some gypsies brought it from India or Jews who immigrated to Turkey from Spain in the 15th century and brought with them many of our traditional performance arts, such as puppets, clowns, illusionists and the “ortaoyunu”. And there are other different theories. Although there may be same elements of truth in all of them, this does not change the fact that it arrived in Turkey from Egypt.

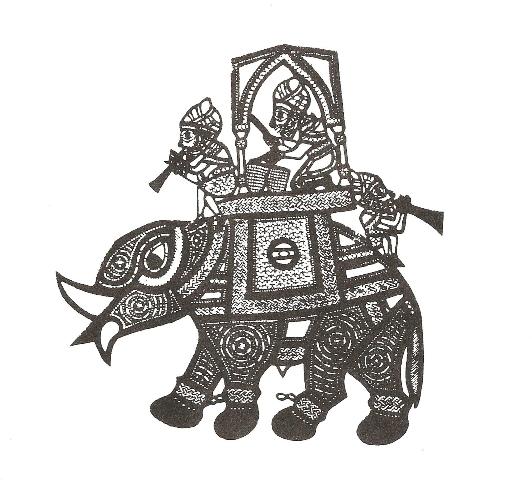

How the shadow play arrived in Egypt is another question. There is a rich and deep-rooted shadow play tradition in Asia, particularly in China, India and Indonesia. Moreover, in China and India the shadow play figures are made of semi-transparent leather, giving them a loser affinity to the Turkish shadow play. However, it is proven beyond doubt that the shadow play technique round its way to Egypt from Java, whose shadow play is the most ancient in all Asia. The famous Moroccan traveller Ibn Battura went to Java in 1345. Long before him, from the 7th to 10th centuries, Arab merchants established colonies on the coasts of Southeast Asia, simultaneously engaging in trade and disseminating Islam. They introduced epics of Islamic origin like the Hamzaname into the culture of Southeast Asia, and in this process of cultural exchange, the Java shadow play was brought to Egypt.

How the shadow play arrived in Egypt is another question. There is a rich and deep-rooted shadow play tradition in Asia, particularly in China, India and Indonesia. Moreover, in China and India the shadow play figures are made of semi-transparent leather, giving them a loser affinity to the Turkish shadow play. However, it is proven beyond doubt that the shadow play technique round its way to Egypt from Java, whose shadow play is the most ancient in all Asia. The famous Moroccan traveller Ibn Battura went to Java in 1345. Long before him, from the 7th to 10th centuries, Arab merchants established colonies on the coasts of Southeast Asia, simultaneously engaging in trade and disseminating Islam. They introduced epics of Islamic origin like the Hamzaname into the culture of Southeast Asia, and in this process of cultural exchange, the Java shadow play was brought to Egypt.

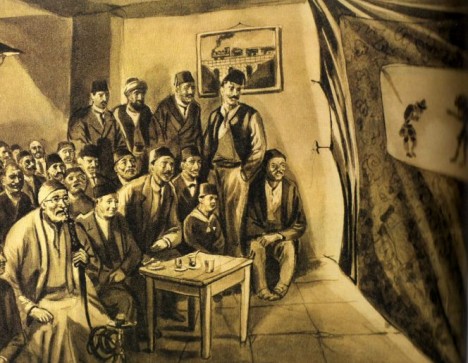

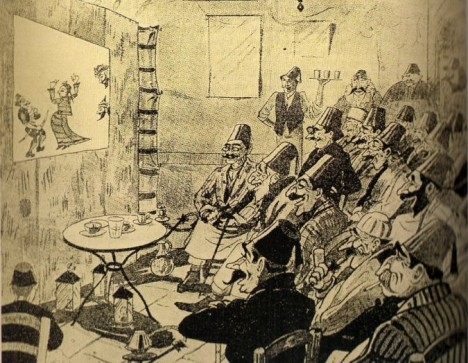

Having taken its basic form in the 17th century, Karagöz went on to develop over later centuries, becoming the best loved performance art, not only among the Turks, but throughout the Ottoman Empire. In the Balkan countries such as Greece, Bosnia, Romania Karagöz was perhaps the most important places for the performances outside of Turkey. Karagöz was also an important part of the entertainment for many years in Cyprus and in North-African countries such as Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and in the Middle East, Syria and Lebanon (Lebanon was part of Syria in this period). Today you can still find Karagöz with a different name (Karagiozis) and style in Greece and South-Cyprus. Before the war in Syria the same art could be found under the name “Karagoush and Iwaz”. In Egypt Aragoz can be found, however, as a hand puppet.

Technique of Karagoz

Regarding presentation, the Karagöz stage is separated from the audience by a frame holding a sheet of any white translucent material but preferably fine cotton, which is called “ayna”, which means mirror. It’s called mirror because the shows are a reflection of reality.

The outer frame of “ayna” is usually a dark coloured textile with flowers. This outer frame is called “çevre”. Çevre means something that covers the surroundings of something.

The size of the screen in the past was 2 m x 2,5 m, however, in more recent times reduced to 110cm x 80cm.

The puppeteer stands behind the screen, holding the puppets against it, using an olive oil lamp as a light source from behind. An oil lamp is preferable as it throws a good shadow and makes the characters flicker thus giving them a more life like appearance. Light is fixed behind and just below the screen. The puppets are put between the light and the curtain on which their shadows are to be thrown. The screen diffuses the light, and the light shines through the multi-coloured transparent material, making the figures look like stained glass. The puppeteer holds the puppet close against the screen with rods held horizontally and stretched at right angles to the puppet. The length of the control rods are about 60cm.

The figures are flat, clean-cut silhouettes in colour. Animal skin is used in the making of the puppets, especially that of the camel. Leather is transparent by itself, so the most important is the fermentation process, which removes the fur. The leather is ready after it has been dried in a dry and windy place.

After the Karagöz figures have been drawn on the leather the edges are cut off. The details inside are cut out with a special knife called Nevrekan. When cutting holes with the Nevrekan pieces of leather will stick out. These pieces are removed with another special knife, which cuts horizontally. These figures are then later painted with water based painting. Today usually china ink, textile paint or Ecoline branded paint is used. There are various books mentioning the usage of vegetable based dyes, however, I haven’t been able to find much information about how these paints were made. I do know that you get a yellow colour when you mix turmeric dust in water or alcohol. Drying an insect called cochineal, taking the dust of it and boiling it with water, on the other hand, make the red colour.

Structure of Karagöz Plays

Each shadow play consists of four segments: (1) Mukaddeme (pro-logue or introduction), (2) Muhavere (dialogue) and ara muha-veresi (an interlude), (3) Fasıl (the main plot) and (4) Outro.

Prologue:

Before the prologue an ornament called göstermelik is moved across the shadow screen. The ornament is a Karagöz figure cut out of one piece of leather. This figure can be a flower, a flower in a pot, a ship, Burak (the horse of Muhammed) and other designs. The ornament is lifted out of the scene while the puppeteer makes sounds from the Nareke (similar to the kazoo) and Hacivat enters while singing and reciting poems. He invites Karagöz, who is not interested in coming. In the end Hacivat is able to convince him to enter the scene, and they fight. Every performance will start like this.

Dialogue:

Karagöz and Hacivat have a conversation about subjects of today’s society. Words of dual meaning and thereby confusion is often the base of the comedy here. This part may contract or expand depending on the skills of the puppeteer.

Fasil:

Fasil is the main story. The themes of the Fasil are either based on love stories, social happenings or super natural stories. Karagöz and Hacivat change their clothes depending on the story. F.ex. in a performance Karagöz is a a café waiter, and will dress as so. In the fasil part, all the characters and minorities can be encountered. F.ex. Çelebi (Gentleman), Zenne (Lady), Laz (Blacksea person), Arnavut (Albanian), Kastamonu (Person from the city of Kastamonu), Ermeni (Armenian), Rum (Greek), Frenk (European), Acem (Iranian), Cadı (Witch), supernatural creatures, various animals and so on.

Outro:

After the fasil Karagöz and Hacivat return to their normal clothes. Karagöz apologizes for any mistakes during the show or if he offended anyone. Before the show ends he also advertises the day and hour of the next show. Karagöz often invites Çengi (a belly dancer puppet) to do a final dance on the shadow screen so the audience leaves with a nice memory.

Characters in Karagöz

Karagöz was a reflection of Ottoman culture and the shadow screen would reflect the cosmopolite culture of Istanbul. A categorized list of the characters of the Ottoman society can be found below. It should be easier to understand the content by this layout.

1) Main characters: Karagöz, Hacivat

2) Women: known as Zenne.

3) Characters with Istanbul dialect: Çelebi, Tiryaki, Beberuhi, Matiz

4) Provincial characters: Laz, Kastamonulu, Kayserili, Eğinli, Harputlu, Kurd.

5) Characters from outside Anatolia: Muhacir (the Immigrant, from Rumelia), the Albanian, the Arab, the Persian,

6) Non-Muslim characters: Rum (Greek), Frank (European/French), Ermeni (Armenian), Yahudi (Jew).

7) Characters with physical or mental defects: the Stutterer, the Hunchback, Hımhım (who speaks through his nose), the Cripple, the Madman, the Cannabis Addict, the Deaf Man, the Idiot (also known as Denyo).

8) Bullies and drunks: Efe, Zeybek, Matiz, Tuzsuz, Sarhoş (Drunk), Külhanbeyi.

9) Entertainers: Köçek dancer (male), Çengi dancer (female), Singer, Magician, Acrobat, Reveller, Illusionist, Musician.

10) Supernatural characters: Wizard, Caddılar (Witches), Djins, Demons.

11) Various occasional secondary characters and children.

Next year (2017) Karagöz will celebrate its 500th birthday. I’m hoping this article will be a gift for this occasion.

Cengiz Özek

Istanbul

1st April 2016

Sources:

Cevdet Kudret, Karagöz. Vol. I. III vols. (İstanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2004).

Nurettin Sevin, Türk Gölge Oyunu. (İstanbul: Büyük Türk Yazarları ve Şairleri Komisyonu Yayınları MEB Basımevi, 1968), 30-38. 110 Siyavuşgil, Karagöz: Psiko-Sosyolojik Bir Deneme, 39-51.

Metin And, Geleneksel Türk Tiyatrosu (Kukla – Karagöz – Ortaoyunu), 1st. (Ankara: Bilgi Yayınevi, 1969)

Metin And, Başlangıcından 1983’e Türk Tiyatro Tarihi (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2006).

Jacob, Türkische volkslitteratur: Ein erweiterter vortrag (Berlin: Mayer & Müller, 1901).

Aydın Öncü, “Karagözle İlgili Araştırmalarda Bir Kaynak Olarak Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi,” A.Ü. Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi [TAED], no. 46 (2011)

Enver Behnan Şapolyo, Karagöz’ün Tekniği (Ankara: Türkiye Yayınevi, 1947)

Ünver Oral, Turkish Shadow Theater: Karagöz, Translated by Cumhur Orancı (Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009)

Sabri Esat Sivayuşgil, Karagöz, Its History, Its Character Its Mystical and Satirical Spirit. (İstanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi, 1961)