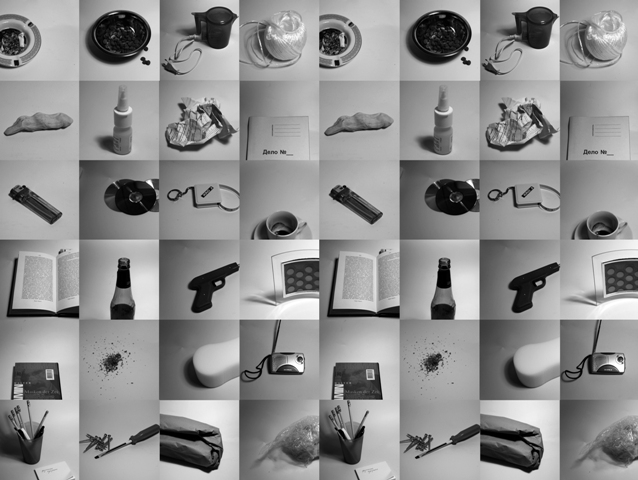

The unusual and revealing Kandinsky Prize exhibition “In an absolute disorder”, commissioned by Andrei Erofeev and Jean-Hubert Martin, is currently on show in Barcelona (until 28 September). The exhibition fills the three floors of the Arts Santa Monica Centre, housed in the building at the end of Ramblas, and it’s one of the most shocking that people have been seen in this dynamic and cosmopolitan arts centre. Shocking because it reveals the extremely critical view of a group of Russian artists about the current reality of their country. An exhibition that merits Titeresante`s attention because of its careful ‘plastic arts’ presentation, between installation, static performance, objects and a wealth of disturbing images.

The unusual thing about the Kandinski Prize is that it manages to avoid the topical, unspeakable uses to which the awarding of prizes is usually put. As Shalva Breus, president of the Foundation ArtChronika and organizer of the exhibition, says:

“The Kandinsky Prize is awarded to Russian artists for achievements in contemporary art. It was founded 5 years ago, and since then it has become a major institutional event in Russian cultural life. Within its foundations and genetic code there are several principles that have enabled its authority and importante to increase rapidly in Russian society.

The Prize is an independent initiative not related to the government. This fact is quite rare and extremely important, as the role of the state in society, including culture, is traditionally outsized in Russia, and there is also a welldeveloped paternalistic relationship between citizens and the state. In addition this Prize is not related to the world of art trading: it is not connected to galleries and auction houses, and does not participate in art fairs.”

The most recent Russian art is presented in this exhibition, the work of artists like Alexander Brodsky, Dmitry Gutov, Vadim Zakharov, Irina Korina, Oleg Kulik, Igor Mukhin, Boris Orlov, Anatolii Osmolovsky, Pavel Pepperstein, Nikolay Polissky, Dmitri Prigov Blue Noses, among others.

On entering the exhibition space you read:

“East is East, and West is West. In the dichotomy praised by Kipling that even today has not disappeared despite globalization, Russia is somewhere in the middle. After the fall of the Soviet empire and rejection of communism, she is once again searching for her identity. Her civil society and cultural features have been washed away like an exposed film. Russia is now more a limbo, a zone of uncertainty, than an affirmation. The key word of this historical moment that, in human concepts of time, could last several generations is: chaos. Social discord, spiritual doubt and material ruin inevitably bring collective psychological and physical wounds. Those currently in power try to assuage these injuries with a surreal mountain of “national projects.” Political parties and the Church compete to compose alluring images of the nation’s future revival. Russian artists, meanwhile, direct their efforts in the opposite direction. They play the traditional role of healers against unchecked power for a society that has suffered under its madness. …The new approach is resignation, restrained acceptance of a disarrayed situation as the local style of culture, thought and behavior. The stylization of chaos in the midst of disorder creates the distance necessary for aesthetic judgment, so desired for freedom of identity, play and choice. This exhibition offers to show various methods for the aesthetic preservation of chaos in works by the newest Russian artists. Despite the difference in their approaches, the images collude to form a new movement in Russian art that remains nameless for the time being.”

The exhibition reflects the Russian reality embroiled in a long and dramatic process of transition and, in turn, reflects our own reality rebound seemingly friendly but chaotic and ruthless whose contours begin to uncover the everyday life of our “crisis”, managed by governments and politicians turned mere puppets manipulated by the dark and not so dark financial powers.

Says Jean-Hubert Martin, curator of the exhibition: “…Art is not reality, and its influence on real life –that of direct action– is very difficult to assess. The life of ideas is so hard to grasp! For twenty years the country has known incredible turbulence accompanied by renewal of violence, therefore the stakes are high to give culture a leading role. Art exists at a distance from the reality of action, and this distance is often expressed through humour. This humour is black, cynical and dry, but what else would it be expected in a country where ideas related to the respect of human dignity are not discussed but resisted by means of physical suppression of militants? The use of humour by Russian artists in such a direct and radical way has created some images that have become famous over the world (and on the Internet). This is a powerful weapon that any authoritarian power fears and it is most difficult to suppress, as it is hit by a laugh at its own expense.….”

For more information on “In an absolute disorder,” see the website ofe Centre Arts Santa Mònica and of the Kandinski Prize. See this video of the exhibition: